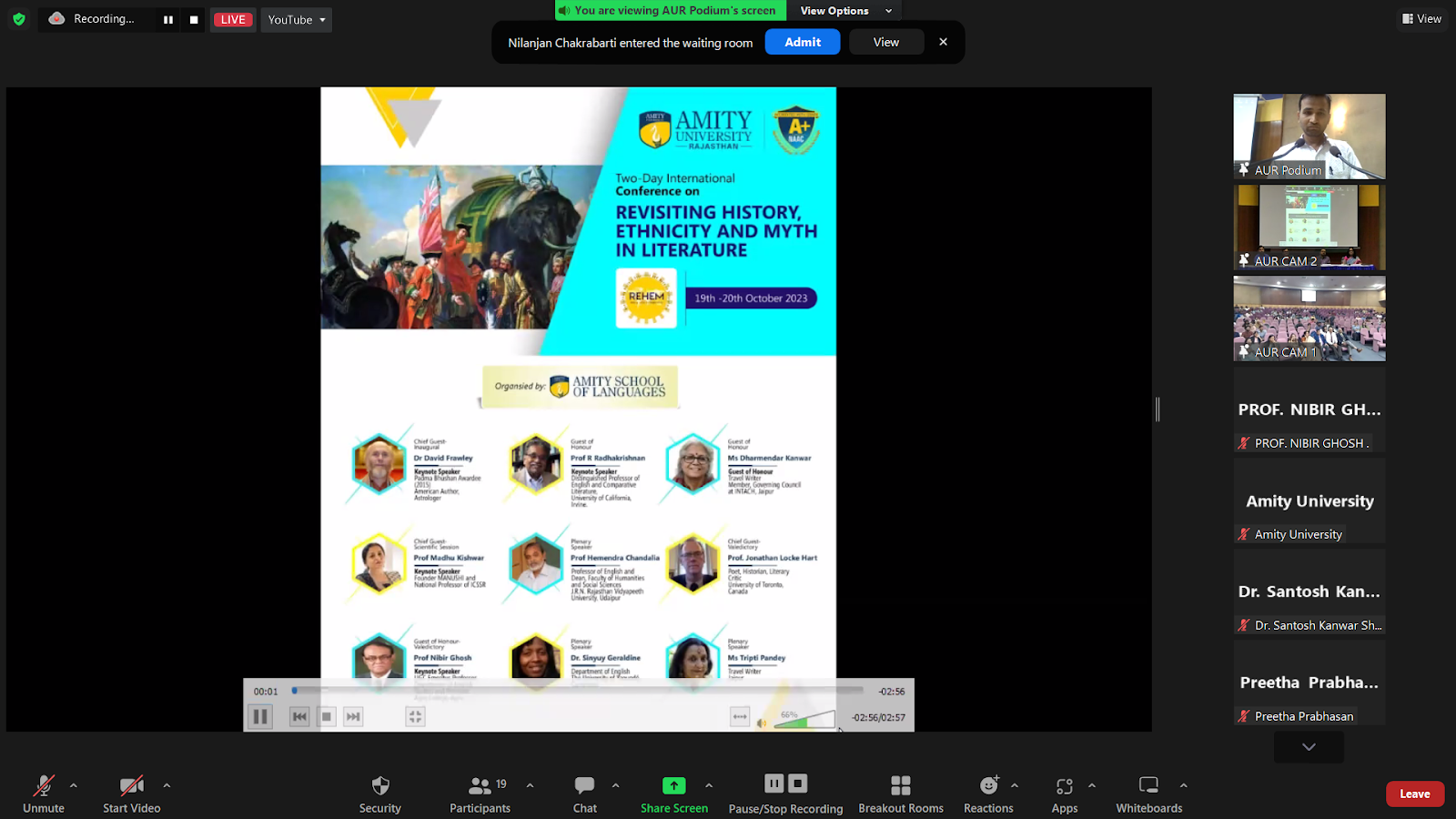

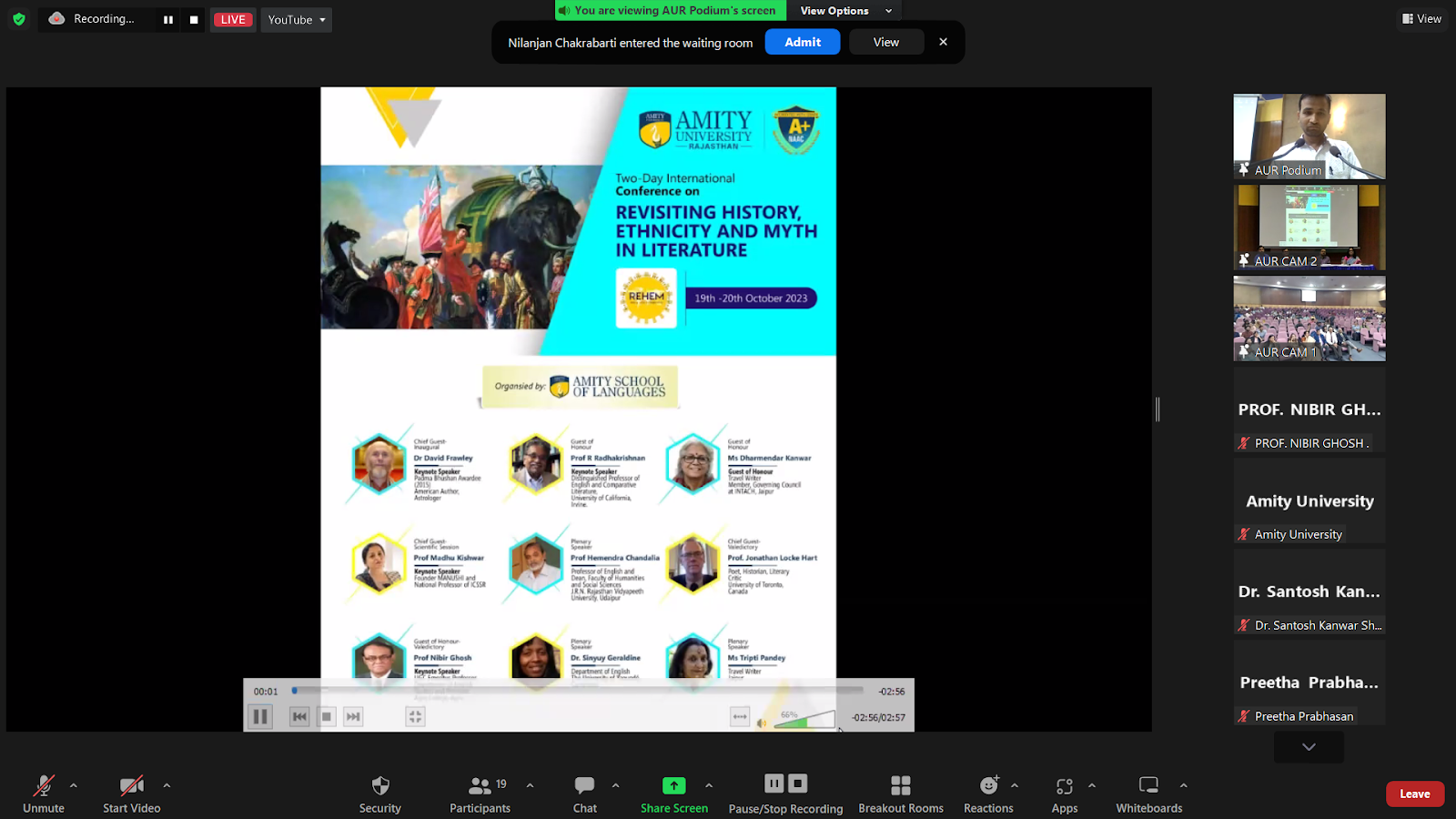

Revisiting History, Ethnicity and Myth in Literature

International Conference

Amity University Rajasthan, Jaipur

19-20 October 2023

History in the

Future Tense: Revisiting Girish Karnad’s Tughlaq

Nibir K. Ghosh

(Keynote Address)

“God, what’s the

country coming to?” This exclamatory statement could very well be taken to be

the lament of any ordinary Indian citizen in the contemporary context. But,

amazingly, it is a statement uttered by an old man at the very outset of Girish

Karnad’s Tughlaq. The scene is the

yard in front of the Chief Court of Justice in Delhi. The year 1327 A.D. Seven

centuries later, disillusionment still seems to be a factor which unifies the

reign of Muhammad-bin-Tughlaq with that of postcolonial India caught in the

vortex of endless crisis.

Girish Karnad (1938-2019), playwright, film-maker, actor

and recipient of Padma Bhushan and Jnanpith awards, published Tughlaq in

Kannada in 1964. Karnad was inspired to choose a historical theme by Kirtinath

Kurtakoti, Kannada writer and critic, who pointed out to Karnad that there were

no plays based on historical themes in Kannada literature akin to Caesar and

Cleopatra and Saint Joan by George Bernard Shaw in English. Anantha

Murthy attributes the reason for Tughlaq’s

appeal to the Indian audience to the fact that “it is a play of the sixties and

reflects as no other play perhaps does the political mood of disillusionment

which followed the Nehru era of idealism in the country” (vii-viii).

“History,”

says E. H. Carr, “is a series of accepted judgments” but “facts and documents

by themselves do not constitute history” (Carr 19). Tughlaq offers a veritable link between received history and its

relevance in the contemporary frame of reference. Karnad’s

protagonist in the play is a faithful portrait and profile of the ruler as

projected in Tarikh-i-Firoz-Shahi by

Zia-ud-din Barani, who figures in the play as both historian and interpreter. It is significant that Karnad’s play offers useful insights

into the inter-textual connection between history, historiography and the

creative mind of the artist to reveal how a historical narrative related to the

society of the past can serve as a key to the understanding of the present.

Girish Karnad’s

essential concern in the play revolves around Tughlaq who was not only the “most

idealistic, the most intelligent king ever to come on the throne of Delhi,

including the Mughals…(but) one of the greatest failure also” (in

Paul 3). The story of the meteoric rise of a monarch endowed with

visionary idealism and the subsequent decline and downfall of this tremendously

capable man within a span of twenty years provided Karnad with an excellent

backdrop against which he could portray, project and foreground the discourse of

visionary politics, the politics of demagoguery, the socio-cultural ethos

governing fundamentalist ideologies and the crisis of a secular nationhood.

In his

“Introduction” to Karnad’s play, U. R. Anantha Murthy rightly avers that

the elusive and haunting quality of the play comes from “the ambiguities of

Tughlaq’s character” related to “philosophical questions on the nature of man

and the destiny of a whole kingdom which a dreamer like him controls” (Tughlaq

vii-ix).

By analyzing the

fateful events of Tughlaq’s times in the context of post-1960s India, Karnad

presents a moving parable of political idealism gone awry whose relevance would

continue in the country’s timeless existence. The manner in which Karnad has

amalgamated the political significance of Tughlaq’s reign with his aesthetic

and emotional response to an Emperor who felt that he alone had the correct

answer shows Karnad’s ingenuity in presenting historical truth beyond the

limits of an academic landscape.

Karnad makes

judicious use of Barani’s account to recreate the paradoxical Tughlaq of

history. Endowed with infinite powers of body and mind,

Tughlaq stands out as the wisest and the most foolish Muslim ruler of India. Tughlaq’s

extraordinary generosity to his subjects and his ruthlessness in getting rid of

the evil doers by putting thousands to death on the slightest suspicion seems a

difficult trapeze-balancing act.

In the opening

scene of the play we find Muhammad Tughlaq expressing his delight and

satisfaction over the manner in which justice works in his kingdom “without any

consideration of might or weakness, religion or creed” (3). His dream is to

perpetuate “greater justice, equality, progress and peace—not just peace but a

more purposeful life” (3). Continuing in his vein of idealism he announces that

to achieve this noble end he has decided to shift the capital of his empire

from Delhi to Daulatabad. His rationale for such a decision is that “Daulatabad

is city of the Hindus and as the capital it will symbolize the bond between

Muslims and Hindus which he wishes to develop and strengthen in his kingdom”

(4). Known the world over for his knowledge of

philosophy and poetry, Karnad’s protagonist, like his historical prototype,

experiences a thrill in imagining the creation of a new world which he intends

to rule not with the power of the scepter in the style of a Muslim

fundamentalist tyrant but by emulating the visionary idealism of the Greeks,

Zarathustra, and the Buddha. Inspired by the Chinese use of paper currency,

Tughlaq introduces copper currency in his kingdom, a scheme that ends in total

failure because of his lack of far-sight in not anticipating its futility in

terms of economic consequences.

Characters like

Sheikh Imam-ud-din and Sheikh Shihab-ud-din and even Barani deeply appreciate

how Tughlaq has done a lot of good work—built schools, hospitals, made good use

of the money (31) but they tell him that he must use all that God has

given—“power, learning, intelligence, talent” to “repay his debt” by spreading

“Islam round the world” (20) instead of trying to become ‘another God’. As his

dreams of ruling by the power of benevolence, justice and impartiality lie

shattered, the philosopher king soon turns into a cruel tyrant. Unable to

sustain his ideology of goodness for long, Tughlaq slides into the morass of

despotism. He proudly celebrates his right to slaughter people, to be known by

his beloved subjects as “Mad Muhammad” and as “Lord of Skins.” He does not

hesitate in asserting that “Not words but the sword—that’s all I have to keep

my faith in my mission” (66).

The naivety of

Tughlaq becomes apparent in his failure to realize how even in his reign

religion is inextricably linked to politics. At the beginning of the play we

find the Announcer informing the crowd of people how Vishnu Prasad, a Brahmin

of Shiknar, has won his suit against the Sultan himself and has received just

compensation for the loss of his land which had been seized illegally by the

officers of the State. In upholding the claim of Vishnu Prasad against his own

authority, Tughlaq feels elated to see how he can dispense justice in his

kingdom irrespective of considerations of might, religion or creed. Shortly

after, we are informed that Vishnu Prasad is none else than Aziz, a low caste

Muslim washerman who, masquerading as a poor Hindu Brahmin litigant, succeeds

in exploiting Tughlaq’s concept of justice and impartiality. Interestingly,

Aziz confesses to his friend Aazam that he chose to masquerade as a poor Hindu

Brahmin simply because “a Muslim plaintiff against a Muslim king” (8) would not

synchronize with the Sultan’s idea of impartial justice.

Through the

various utterances of Aziz, Girish Karnad skillfully portrays the relevance of

what, in contemporary parlance, we call politics and diplomacy. Aziz tells

Aazam:

You have been in Delhi for so many years and you are as stupid as ever.

Look at me. Only a few months in Delhi and I have discovered a whole new world.

Politics.-- My dear fellow, that's where our future is -- politics. It's

a beautiful world -- wealth, success, position, power -- and yet it is

full of brainless people, people with not an idea in their head. When I

think of all the tricks I used in our village to pinch a few torn clothes from

people -- if one uses half that intelligence here, one can get robes of power..

-- it's a fantastic World. (50)

In order to be successful in politics, Aziz offers the reader/audience a

prudent recipe that is as relevant today as it was in the reign of Tughlaq:

A man must commit a crime at least once in his lifetime. Only then will

his virtue be recognised. Listen. If you remain virtuous throughout your life

no one will say a good thing about you because they won't need to. But

start stealing -- and they will say: 'What a nice boy he was but he is ruined

now.' Then kill and they will beat their breasts and say: 'Heavens! He was only

a petty thief all these days. Never hurt anyone. But Alas! Then rape a woman

and the chorus will go into hallelujahs: He was a saint and look at him now.'

Aziz doesn’t stop at that. He logically spells out his

long-term goals: “You rob a man, you run, and hide. It's so pointless. One

should be able to rob a man and stay there to punish him for getting robbed.

That's called ‘class’ – that’s being a real king” (58).

In Tughlaq’s rule

it was possible for ordinary mortals like Aziz to exploit the politics of

communalism to gain a stretch of land and to manage a post in the civil service

“to ensure him a regular and adequate income” (3). In contemporary India the

likes of Aziz may exploit similar situations to reach the apex in the pyramid

of power. With a little astuteness it has become possible to use religion or

caste in controlling the nerve centres of power. It is little surprising that

even today elections in India can be won or lost on purely communal or caste

lines. Money and muscle power are vital supplements for acquiring power. If one

has a proven criminal record, he is bound to be respected and worshipped by his

followers.

While advocating

the secular cause, Tughlaq never seemed to have realized that his idealism

would set him up against the Amirs, the Ulema, and the Sayyids who did not

appreciate the ruler’s lack of fundamentalism in approaching the holy Koran. Tughlaq wanted to command by the

power of trust and understanding but the vitiated atmosphere of a court

dominated by the communalization of politics makes him ask Barani sadly: “Are

all those I trust condemned to go down in history as traitors? Tell me…will my

reign be nothing more than a tortured scream which will stab the night and melt

away in the silence?” (43). The ruler who began with the “hopes of building a

new future of India” has learnt to solve “all problems in the flash of a

dagger” (42). Tughlaq’s act of shifting his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad

and back again to Delhi suggests the tragic attributes of his nemesis.

Tughlaq’s attempt

to propagate communal harmony between Hindus and Muslims may be an excellent

recipe for the symptomatic malaise of both fourteenth century and contemporary

India, but such notions of harmony were then, as are now, nothing but

transcripts of utopian dreams. The seeds of disorder afflicting society on

communal lines seem to have been sown centuries ago. Nurtured and nourished by

mutual hatred and violence, these seeds of dissent ultimately led to the

partition of the subcontinent, the after-effects of which can be witnessed at

regular intervals, be it a scene of a riot or an India-Pakistan match in a

stadium.

The play also

tells us that the introduction of religion into politics to secure power over

the masses by arousing their political consciousness appears to have become a

dominating factor in the game of power politics. The contemporaneity of

Karnad’s play emerges from his identification of the variables and the

constants which have controlled the power equation ironically in the world’s

largest democracy. Through a series of events Karnad shows how power, once

rooted, is not easily shaken. Once a demagogue fails in transforming power into

authority, the waning consent of the governed compels the demagogue to assume

the role of a cruel and relentless despot. Tughlaq takes recourse to methods of

coercion to legitimize the power that he wields.

Tughlaq emerges as

a shrewd politician who has learnt the art of transforming every adverse

situation to his advantage. He invites the charismatic religious leader

Imam-ud-din to address a public meeting and gives him the freedom of denouncing

the policies of Tughlaq in public. The act may appear to exemplify Tughlaq’s

courage and integrity in allowing freedom of expression to prevail in his

kingdom. This façade of impartiality and supreme objectivity comes to the fore

when we learn in the play that his soldiers have been sent from door to door to

prevent them from attending the said meeting.

Tughlaq’s tragic

tale is symptomatic of the inherited complex problems of Indian society. Time

and again it has been proved that mere idealism, unrelated to the understanding

of the times, cannot by itself help in reaching visionary heights. The ever-increasing

criminalization of politics characterized by the power of might over right is

indicative of the failure of ideals that the freedom fighters had envisaged for

the country. The play also goes on to show how hard measures imperative to the

progress of the nation can never find acceptance with either the players of the

power game or with the common populace. Rampant corruption has made the ideals

of honesty anachronistic. In a society poised between secular and

fundamentalist ideologies, the parameters of Tughlaq’s world bear close

resemblance to the discourse of the Indian political and culture experience

despite there being essential differences between the characteristic features

of the fourteenth century and that of modern India.

In conclusion, it

may be accepted that Karnad’s powerful play rightly reminds us of what George

Santayana warned us about in 1905: “Those

who cannot

remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Thank

You!

Revisiting History, Ethnicity and Myth in Literature

Nibir K. Ghosh

Guest of Honour Valedictory Note

History

In a Paris Review interview Chinua Achebe referred to an old African proverb that says,

“Until the lions have their own historians, histories of the hunt

will glorify the hunter.” In the same interview, Achebe said that storytelling "is

something we have to do, so that the story of the hunt will also reflect the

agony, the travail—the bravery, even, of the lions."

“The

study of history is a study of causes,” says E. H. Carr in his iconic book What

is History and adds that the great historian or the great thinker “is the

one who asks the question ‘Why?’ about new things or in new contexts.” I am

sure most of us are familiar with concepts like ‘Erasure’, ‘Bleaching’ or

‘whitening’ of History that form the lexicon of contemporary discourse. It is

necessary to revisit History and ask questions rather than take things, events

and opinions for granted.

Ethnicity

For substantiating the contemporary significance of ethnicity, I

would like to share two instances. One relates to the event in which a French policeman shot and killed Nahel Merzouk, a

17-year-old boy at a traffic checkpoint in Nantarre, a suburb of Paris

resulting in widespread riots in France and other countries. According to the

testimony of Nahel’s beloved mother, the police officer who shot him "saw

an Arab face, a little kid, and wanted to take his life." The Nahel incident brings to our mind a similar event in Minneapolis, Minnesota where

George Floyd, a Black man, was murdered by Derek Chauvin, a 44-year-old white

police officer, on 25 May 2020. In this context of ethnicity issues, the recent

saga of Manipur burning is again no exception.

Myth

Writers have always been fascinated by the remoteness, mystery

and heroism of myths. Carl Gustav Jung has stated that the materials of myths

lie in the collective unconscious of the race. Inspired by the myth embedded in

Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, written 2500 years ago, Sigmund

Freud revolutionised human thought by coining what is now universally known as

the Oedipus complex.

Similarly, Prometheus the Greek

god, who was chained to a rock for helping mankind with fire, has been the

source of inspiration for numerous works of immortal fame. A case in point is

Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer

that is based on the biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American theoretical

physicist credited with being the "father of the atomic bomb,” entitled American

Prometheus: jointly authored by Kai Baird and Martin J.

Sherwin in 2005.

Literature

“An unexamined life is not worth living” said Socrates at his

trial, a task for which he was punished to die by drinking the hemlock. I

believe that nothing helps us examine life as literature does. Therefore, as

writers, academics, scholars and researchers it is incumbent upon each one of

us to meaningfully apply ourselves to take forward the ideas and approaches

provided by this successful international conference. To those who doubt the

efficacy of literature in transforming lives at a critical time like the one we

live in, I would like to share a statement by Salman Rushdie:

“A poem cannot stop a bullet. A novel can’t

defuse a bomb. But we are not helpless. We can sing the truth and name the

liars.”

.png)

.png)